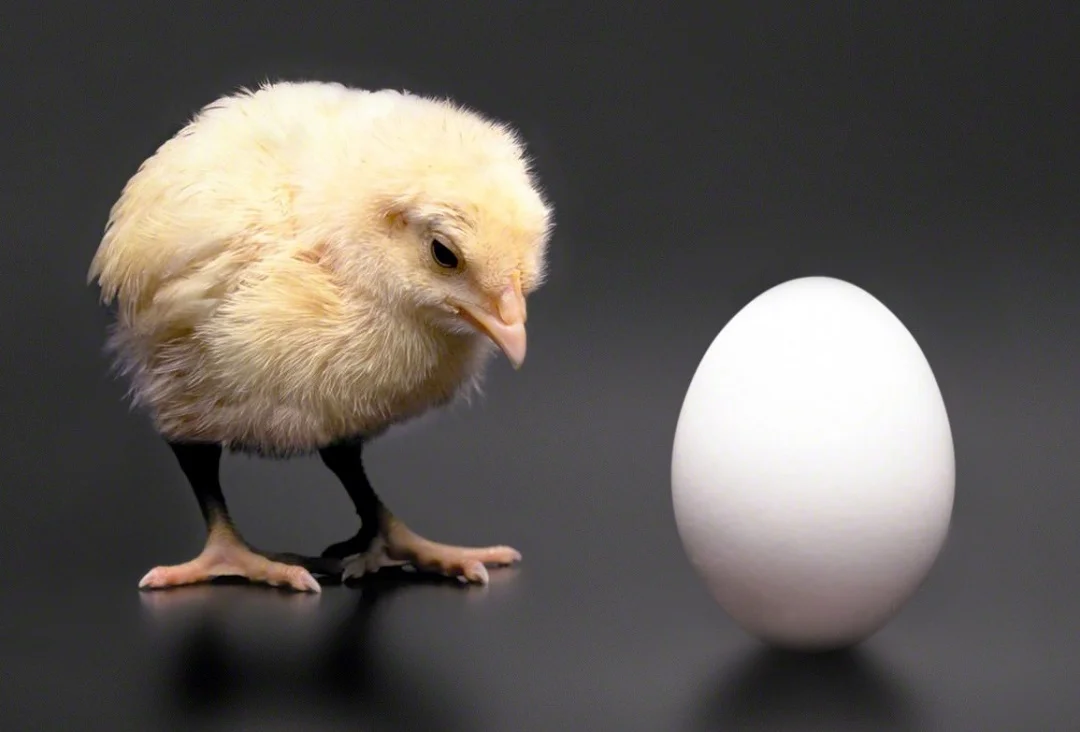

The Chicken and the Egg?

In Darwin’s days, cellular life was viewed as simple. So much so that all that was believed to make life was water or exposed organic material. Rotting meat produced maggots. Old bread produced weevils. Spontaneous Generation was the theory of the land.

Today’s worldview is completely the opposite. Using proton and electron microscopes, we now see very complex molecular machines in each and every cell in our bodies. Machines that seem intricately designed to perform their respective functions according to the scores of instructions, information, and meta-information encoded in DNA.

For naturalistic worldviews, this presents one gigantic problem. How did all the information and meta-information required to run & reproduce a cell, and all the molecular machines that are able to understand and execute the instructions within that information, first arise? And which came first, the information or the machines?

It sounds like the classic chicken and egg problem. Except it isn’t. The machines that run a cell are useless without the information, and the information is useless without the machines. It’s the same as if I handed you a hard drive with all the software to run a computer. Without a computer to read and execute the programs, the hard drive is useless, and vice versa. These mutually defining parts need each other to make and function as a computer. It’s the same with the cell. There’s no getting around that. We need the chicken and the egg.

How have the evolutionists explained all this? They haven’t. All we’ve gotten are assertions that the first cell was nothing more than a happy accident. It’s all just a product of randomness and chaos. And they say this like it’s not only a plausible answer, but the most plausible answer. Unfortunately for them, the natural tendencies of chemistry and physics say otherwise. As we continue to learn more, especially in the realm of microbiology, things are continuously getting worse.

Although evolutionists still refuse to relinquish their treasured belief of abiogenesis, most acknowledge the shear improbability of it. If only just to try and dismiss it. Richard Dawkins loves this line of thought so much he takes a two-fold approach.

First, he argues that breaking up the gigantic hurdles that evolution has to clear into many smaller, more probable scenarios makes it more likely. Which doesn’t work when your driving engine is randomness and the target is order, it actually makes things worse. A point which in part he realizes, leading to his second argument; we live in a multiverse filled with a multitude of universes. And by multitude he means 1 x 10 to the 500th power. That’s an absolutely humongous number, a one followed by five hundred zeroes, of massive universes. Of course, he doesn’t know how many universes are out there, or if there’s anything beyond our universe at all. He’s simply making a philosophical argument that tries to tip the scales of probability. The fact he feels compelled to make this argument is telling. Either he himself believes it preposterous and is in denial about it, or he believes that explaining a preposterous proposal using preposterous philosophy will somehow make it believable. Maybe a mixture of both?

In any case, arguments like these from prominent scientists at prominent universities are causing a lot of people to lose faith in the scientific community. Ever hear the saying, “The problem with science is that so much of it isn’t”? That’s precisely the case here.