The Unnecessary Fall of Happiness

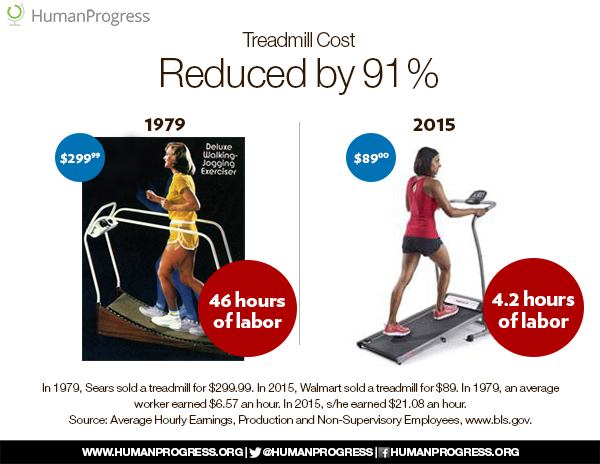

Today’s America has never been more pampered. Throughout most of the country, an average American can order nearly any household product without leaving their couch, let alone their powered, plumbed, air-conditioned home, and expect it to arrive to their doorstep within two days. Over the last few decades, most of those products have gotten substantially better: Cars and trucks are much more efficient, comfortable, and have more amenities; homes are larger, more comfortable, and functional; most of the goods and services we consume share that same trend, they’ve gotten better overall in nearly every category, if not all. To color just how far we’ve come, here are a few comparisons of common household items from 1979 and 2015. Note the differences in quality and the cost in hours worked:

Our economy serves our demands better, but what about income? There too, the metrics paint a rosy picture. Wealth and income growth since the 1980s has been widespread across all demographics, especially when factors such as non-wage benefits are included. Ben Shapiro stated this well in a recent Newsweek article, in which he dispelled the wage-stagnation myth:

Supposedly, we are in the midst of a great economic slump, in which people who work hourly haven’t gained one iota for some forty years, while those who work on Wall Street have cleaned up. Economic mobility, the argument goes, has declined; we’ve been divided into a hierarchical structure from which non-elites cannot escape.

The key data point in this argument is wage stagnation since 1979. Since 1979, the average hourly wage for American workers hasn’t risen, yet the salary for workers in white collar professions has risen dramatically. This is evidence that an entire class in the United States has been left behind.

But what if that statistic is fatally flawed? What if it turns out that those who aren’t in the top 1 percent or the top 10 percent have benefitted [sic] remarkably from globalization and liberalization of regulation?

That happens to be the truth. As it turns out, there are several factors that simple wage statistics ignore. For example, as Marian L. Tupy points out at Reason.com, non-wage benefits have expanded dramatically since 1979—so dramatically that “they could amount to as much as 30 or even 40 percent of the workers’ earnings.” Those non-wage benefits include everything from paid vacation to health care coverage. Economist Edward Conard explains in his book The Upside of Inequality:

"Misleading income measures assume tax returns—including pass-through tax entities—represent households. They exclude faster-growing healthcare and other nontaxed benefits. They fail to account for shrinking family sizes, where an increasing number of taxpayers file individual tax returns. They don’t separate retirees from workers. They ignore large demographic shifts that affect the distribution of income. Nor do they acknowledge that consumption is much more evenly distributed than income. More accurate measures show faster income growth, especially for non-Hispanic workers, and wage growth that parallels productivity growth."

So basically, since the 1980s, people are making more money, are able to buy higher quality things at cheaper prices, and get them more conveniently and oftentimes faster. And the innovation doesn’t stop there: information is no longer confined to libraries and television; communication is far easier, with many different mediums now available to converse with friends and family through, including video chat, which most people are able to do anytime with their smartphones; and entirely new economies have opened up, providing an even more diverse array of opportunities. On the risk front, violent crime and unemployment are at lows, the economic metrics indicate stability and growth, even car accidents inflict less bodily harm thanks to safety equipment improvements. Nearly every metric points to better quality of life.

All that considered, the populace should be much happier, but that’s not what we’re observing. Data from self-reported happiness levels, gathered in generic surveys, have shown modest decreases over this same period, but these are derived from simple questionnaires. Taking deeper dives into other, more reliable metrics that are derived from the study of self-destructive behavior, mood disorders, and depression confirm the same trend, but much more pronounced. We see extensive rises in the majority of self-destructive tendencies associated with unhappiness (drug & alcohol abuse, hyper-promiscuity, self-mutilation & eating disorders); and the number of diagnoses for anxiety and depression, increasing by orders of magnitude in some areas.

It’s gotten so bad that exact quantification has become unnecessary. The problem is that obvious. We now have over a quarter of the country’s adults on mood-altering prescription drugs; and the doses are so high that the accumulation of the trace amounts expelled in urine have begun to affect species of fish in the Great Lakes. Drug use, particularly hard opiates, has also surged to record levels (see below for a comparison of where we stand against other countries), which are in fact so high that they are the primary reason that the country’s life expectancy fell year-over-year. Suicides also increased, jumping 14% from 1990 to 2015 among the general populace, and the most of those gains resided within the younger and more affluent demographics, which should be the happiest of all.

DALY = Disability Adjusted Life Years, or the number of years lost to ill-health, disability, and death per 100,000 people.

This is what’s known as the Easterlin Paradox. Basically, as life gets better, the populace becomes less happy, develops more mental health disorders, and becomes more self-destructive. Such a conundrum goes against much of what we intuitively believe about human behavior. Why humanity behaves this way no one knows for sure, but there are many theories offering explanations. Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University concludes in his newest report (released March 20, 2019) that the problem is addiction itself. His corrective actions call for quite a few additional governmental restrictions on an array of industries ranging from pharmaceuticals to commercial advertising. His report is part of a larger compilation called the World Happiness Report 2019. The other coauthors’ conclusions also recognize the fall, but blame other things ranging from social media and obesity, to people’s leisurely behaviors. Some of these have merit, and the correlations are strong when it comes to digital media consumption.

Ultimately, their recommendations are shallow. They fail to address the real problem; and enacting them will have a marginal effect on happiness at best. The real problem is much more foundational and philosophical than that. For example, say a person identified their looks as a major contributor to why they feel unhappy. The authors recommend a string of fixes that range from self-improvement to regulating commercial advertising that may emphasize those feelings of inadequacy. But the real question is, why do they feel inadequate at all? What makes a person’s looks an integral component that determines whether they are happy or not?

The answer is surprisingly simple: It can be an integral component if, and only if, a person chooses it to be. Therein lies the key to happiness, being able to recognize and harness the power of the mind to choose the conditions that dictate how, and at what thresholds, happiness and contentment can be achieved. Often times, the mere act of deciding on conditions, assigning attainable goals, and then pursuing them lifts spirits remarkably. There is solace to be found in the pursuit of happiness, and stability in choosing the conditions of happiness.

Of course, for many, choosing happiness is easier said than done. There are a lot of people who simply don’t know how, and many more that don’t even believe it is possible, but there are many ways that it can be done. Altering perceptions, changing priorities, and setting & pursuing goals are just a few of the options. Granted, there are limits. Someone who is struggling to satisfy the lowest elements of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs isn’t going to be able to override the desires for basic necessities. The body still needs food, water, rest, and shelter; nothing will change that, nor that misery naturally derives from missing them. But, the fact remains that for most, the mind can choose happiness at points above that. In the developed world, that means for most people, the only thing standing in the way of happiness, is the person in the mirror.